I’d wanted to write an article on Zen in the martial arts for a while now. I hadn’t done it because I always felt I hadn’t read enough or knew enough about the subject.

Silly me. I should have been okay with not knowing.

Recently a friend of mine recommended a book called The Book of Not Knowing by Peter Ralston. Ralston is a martial arts master and Zen teacher. In 1978 he became the first non-Asian to win the World Championship full-contact martial arts tournament in China. He runs the Cheng Hsin School of Internal Martial Arts and Center for Ontological Research in Oakland, California.

I must admit that the fact that he had won the tournament peaked my attention. Ralston himself makes a point of it in the book. He says that most people seek him out because he’s a martial artist and even because he had won that tournament.

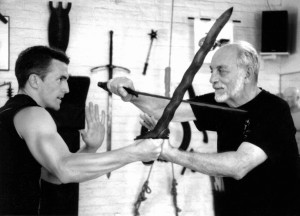

Ralston at the 1978 World Championship in China.

Ralston at the 1978 World Championship in China.

Funny how we operate. As soon as we see a martial artist accomplish an amazing deed we immediately want to milk them for information.

Ralston’s book, as the title very clearly indicates, talks about the benefits of not knowing, or that state of mind we’re in before we make a discovery.

Not knowing has gotten a bad rep in our society because we equate it to stupidity. But that doesn’t need to be so. It can be a state of openness and freedom.

Ralston goes on to tell us how our sense of self is attached to our beliefs and these come to us through upbringing, books, learned behaviors, etc.

These ideas are not us, they are only beliefs. Yet these beliefs sometimes do the thinking and reacting for us.

In the book Ralston gives us a little exercise that I would like to share with you. It’s an interesting one.

See if you can figure out how many things you actually know from personal experience.

Eliminate everything learned out of a book or that somebody’s taught you, even if you know it to be true. If you haven’t experienced it firsthand it shouldn’t make the list.

That means that for example, knowing that the Earth is round shouldn’t make the list, because even though you know it’s true, you have no way of experiencing it.

Stick to things you know by personal experience.

Try it. I think you’ll be surprised by the outcome.

Many times we anticipate what the outcome of an encounter might be because all that learned behavior is telling us that it’ll turn out one way instead of us actually experiencing how it will turn out.

We run to what we know. Zen teaches us how to do without these preconceptions, from a purer sense of who we truly are.

Next time you get mad at someone; don’t just react in a way that you think appropriate. Really look at what the person did and see if you’re really mad at all. You’ll be surprised how much anger is a learned response.

The great Joe Hyams in his wonderful book Zen in the Martial Arts talks about his first meeting with Bruce Lee:

“’Do you realize you will have to unlearn all you have learned and start over again?’ Bruce said.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘You want me to empty my mind of past knowledge and old habits so that I will be open to new learning.’

‘Precisely,’ said Bruce. ‘And now you are ready to begin your first lesson.’”

The passage brings to mind the great difficulty westerners have in grasping some of the principles of Zen.

Zen and the martial arts are intimately intertwined. The learning process is not linear, it’s experiential.

We strive to achieve that emptiness of not knowing from which we can react to anything in a unique and authentic way. This is the nature of all the arts.

Eugen Herrigel in his seminal Zen in the Art of Archery says:

“Art becomes artless…shooting becomes not shooting, the teacher becomes a pupil again, the master a beginner, the end a beginning and the beginning perfection.”

Every once in a while in your training you will have a revelation of what your true self is really like – that moment when your arms and legs seem to move on their own, without fear, without thought, but with deadly precision.

When that happens, remember you are practicing Zen, and you’ve just had a glimpse of your true self.

I’ll leave you with an old Zen tale, also from Hyams’ book. It’s one of my favorites:

TRY SOFTER

A young boy traveled across Japan to the school of a famous martial artist. When he arrived at the dojo he was given an audience by the sensei.

“What do you wish from me?” the master asked.

“I wish to be your student and become the finest karateka in the land,” the boy replied. “How long must I study?”

“Ten years at least,” the master answered.

“Ten years is a long time,” said the boy. “What if I study twice as hard as all your other students?”

“Twenty years,” replied the master.

“Twenty years! What if I practice day and night with all my effort?”

“Thirty years,” was the master’s reply.

“How is it that each time I say I will work harder, you tell me that it will take longer?” the boy asked.

“The answer is clear. When one eye is fixed upon your destination, there is only one eye left with which to find the Way.”